A Bird's Eye View of the Salisbury Confederate Prison

I promised you a continuation of the story about the Salisbury Confederate Prison, so here it is!

In 1861 President Abraham Lincoln demanded that North Carolina send troops to help defeat the Confederate army and force the secessionist states to return to the Union. The governor of North Carolina, John W. Ellis, a Salisbury native, responded to the president saying,

“I regard the levy of troops made by the administration for the purpose of subjugating the Sates of the South as in violation of the Constitution and a gross usurpation of power. I can be no party to this wicked violation of the laws of the country, and this war upon the liberties of a free people. You can get no troops from North Carolina.”

A Salisbury native, John W. Ellis (November 23, 1820 - July 7, 1861) was the governor of North Carolina at the start of the American Civil War. He was forced to resign because of failing health and died shortly after the war began.

On May 20 of that year North Carolina seceded from the United States and joined the Confederacy. Shortly thereafter the Confederate government began looking for a site for a Confederate Military Prison.

Eventually the Confederacy settled on a sixteen acre site in Salisbury. The main building on the site was a derelict cotton mill that had been owned by Maxwell Chambers. For a short time this building housed a boys’ academy and had also been a meat packing plant for the Confederacy. The site was also the general muster ground – a fancy term for the local recruiter’s office! It was located next to the main line of the railroad that ran through Salisbury. The building was sturdily built of brick and was three stories tall with an attic. The Confederate government purchased the compound for $15,000. Once it became a prison, a wooden stockade was built around the perimeter of the sixteen acres.

This old mill was the central building of the Salisbury Confederate Prison.

On December 9, 1861 the first prisoners of war entered the Salisbury prison. There were 120 soldiers in this first group. By the following May the population in the prison was 1,400. At that point in the war life in the Salisbury prison wasn’t too bad. One prisoner wrote that it was, “more endurable than any other part of Rebeldom.” Inside the compound there were lots of shade trees and plenty of water.

A Copy of the Prison Rules

The prisoners were able to occupy themselves in a number of diversions including whittling, trading, and writing. They even played baseball! One prisoner wrote that they played baseball nearly every day that the weather would permit it.

Earlier in the war conditions inside the prison weren't so bad. There was time (and room) for recreation. This painting is one of the oldest known pictures of a baseball game being played. There are claims that this was the first baseball game played in the South!

Throughout most of the war the prisoner exchange program between the North and the South helped to keep the prison at Salisbury from becoming too crowded. In fact, up until 1864 there were more disloyal Confederates, Confederate and Union deserters, and Confederate and civilian criminals in the prison than there were Union POWs! Due to paroles and the prisoner exchange program, the Salisbury Prison was little more than a stopping point on the way home for Union POWs.

All of that changed in August of 1864. The United States government decided to halt all of the prisoner exchanges. That decision, along with an influx of POWs from recent battles caused the prison’s population to quickly swell from 1,400 to 5,000 men in October of 1864 – double the prison’s safe capacity. Within a month things would get worse. An additional 5,000 prisoners were sent to the prison in November. 10,000 men were jammed into a space designed for 2,500. There were 5 times more men inside the prison than there were citizens living in Salisbury at that time! As you can imagine, the disparity in these numbers was a great cause of concern for the civilians living there.

The Union blockade of Southern ports made it increasingly difficult to get adequate supplies to the army and civilians, let alone prisoners of war. However, even though things were tough outside of the prison, Salisbury’s citizens weren’t without compassion. They often took clothes and food to the prison. They also petitioned the Confederate Secretary of War to move half of the prisoners to help alleviate the shortage of shelter, food and water. They were even able to get Governor Zebulon Vance to negotiate with the Federals (after several attempts) for clothing for the prisoners.

One citizen was especially well known for her humanitarian efforts at the prison. Mrs. Sarah Johnston lived just outside the walls of the prison. She cared for many within the walls of the prison and even provided nursing care to men from both the Confederacy and the Union in her own home. She even had one young man, a Union soldier named Hugh Berry, who died in her care buried in her garden to prevent him from being buried in the unmarked mass grave that was being used by that time.

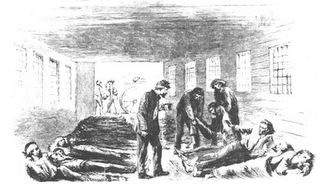

As the prison became extremely overcrowded in the last days of the war, conditons deteriorated for prisoners inside the compound. Disease and starvation claimed thousands of lives.

Prior to the US government’s decision to stop all prisoner exchanges, the death rate in the Salisbury prison was only about 2%. However, after these exchanges were halted the crowded conditions in the compound caused communicable diseases to run rampant, and so many were affected that it became necessary to convert all of the prison’s structures into hospitals. That meant that the healthy prisoners had to sleep outside in tents if they could get them. Many resorted to digging holes in the ground for shelter. The winter of 1864 and 1865 was particularly cold and rainy, exacerbating an already intolerable situation. The lack of medicine, shelter, clothing, and food (caused by the Union blockade) led to the unnecessary sickness and deaths of thousands of prisoners. The death rate quickly climbed to 28%. Conditions were so bad inside the prison that even the guards refused to go in.

The conditions within the compound turned all thoughts to try to find a means of escape. Some were able to tunnel their way out, but only about 300 prisoners managed to escape from the prison. It is also estimated that 2,000 prisoners defected to the Confederacy to escape the horrors of the prison.

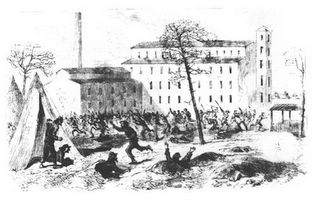

On Friday, November 25, 1864 the most ambitious and organized escape attempt ended tragically. Prisoners goaded on by starvation, disease, lack of shelter, and particularly brutal weather attempted to rush the main gate. The gate cannon was fired three times to quash the revolt and approximately 250 men died from the wounds they received.

On November 25, 1864 thousands of desperate prisoners attempted to overrun the guards. The guards fired the gate cannon into the mob three times, quelling the revolt and instantly killing 53 men. All told, 250 men died from the initial cannon fire and from wounds received in the uprising. One of those killed in the attempted escape was Robert Livingstone (alias Rupert Vincent), the son of abolitionist David Livingstone.

Two well known journalists from the New York Tribune, A.D. Richardson and Junius H. Browne, were being held in Salisbury and managed to escape during this time. The articles that they wrote when they returned to New York made the Salisbury Prison notorious, but they helped to change the Union policy about prisoner exchanges.

Prior to the winter of 1864-65 dead prisoners were buried individually in a coffin in a marked grave with military honors; however, as the conditions deteriorated inside the prison it became necessary to bury them in unmarked mass graves. The dead were moved to “the dead house” where they were counted and loaded onto a wagon. They were then taken to a corn field where they were buried in long trenches.

An end marker for one of the mass graves at the Salisbury Historical National Cemetary. There are 36 such markers at the cemetary marking the head and foot of 18 trenches measuring 240 feet long used to bury prisoners who died during the winter of 1864-1865 at the Salisbury Confederate Prison.

By the time that the prison stopped operation 18 trenches 240 feet long were required to bury the dead. These graves eventually became the Salisbury Historic National Cemetery. It is estimated that between 5,000 and 11,700 men died in the prison. (“However, Louis A. Brown, author of The Salisbury Confederate Prison, stated after years of research that there could be no more than 5,000 who died at the Salisbury Confederate Prison.”)

Salisbury's Historical National Cemetary

In February of 1865 a new prisoner exchange policy was negotiated. 3,729 able bodied soldiers were marched to Greensboro, NC where they were sent by train to Wilmington, NC where they waited for their exchange. A second group of 1,420 of the sickest prisoners was sent to Richmond, effectively ending the compound’s use as a prison. It was then converted to a supply depot.

General George Stoneman (August 22, 1822 - September 5, 1894) led a raid through western North Carolina in 1865 in support of Sherman's Carolina campaign. He eventually reached Salisbury where he burned the Confederate Prison to the ground. He eventually became governor of California.

On April 12, 1865 General George Stoneman attacked Salisbury to liberate the prison, destroy Confederate supplies and destroy the Yadkin River rail bridge. General Stoneman didn’t realize that the prisoners had already been released from the prison due to the damage to telegraph lines. (In fact, he didn’t even realize that the General Lee had surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox three days earlier.) He had the prison and all Confederate government buildings and supplies burned, but spared the Salisbury Court House – an act that is the subject of much speculation and local legend. I will address this story at a later time. The bricks from the prison were later sold, and story has it that many of the homes on South Main Street contain brick from the Confederate Prison.

Local residents weren’t sad to see the prison go. One citizen said it best, "No one was sorry when the Yankees made a bonfire of the evil-smelling empty, dolorous prison, the scene of so much unalleviated suffering and so many deaths. This chapter could only be appropriately closed in a purification by fire."

The only remaining structure from the Salisbury Confederate Prison. The home is now an antiques store.

The only building that remains from the Confederate Prison is a house located in the 200 block of East Bank Street. The house was originally built as a story and a half log home by William Valentine – a free black man who was a banker. During the time that the prison was in operation, the house served as a guardhouse. The house is now a really interesting antique shop only open on Thursdays.

In future articles I will discuss General Stoneman’s raid on Salisbury as well as some of the other key players from the prison like Dr. Josephus Hall, the prison surgeon! Below are links to the websites that I found particularly helpful in providing the information that I used for this post.

http://salisburyprison.gorowan.com/

http://www.salisbury.net/scpa/Rowan_Co.html

http://www.salisburyprison.org/PrisonHistory.htm

http://www.tradingford.com/stoneman.html

http://www.rowanpubliclibrary.org/HistoryRoom/prison/salsprison.htm

http://www.salisburync.gov/prison/1.html

http://www.salisburync.gov/prison/2.html